A model for secondary school education in Guernsey featuring three schools, covering ages 11 to 18, with each offering both GCSE and A-level qualifications, seems to be viable if specialisation is accepted at A-level for two of the three schools.

This would produce three schools with equal status: there would be no school that could be considered “superior” to the others, as had been the case with the 11+ selection in place, where the Grammar School offered a wider curriculum choice and was often considered to offer a better standard of education in general.

All schools would offer a broad and balanced education at GCSE level. For A-levels, two of the schools would have specialisations, and that could also add areas of additional strength into the GCSE provision for those schools.

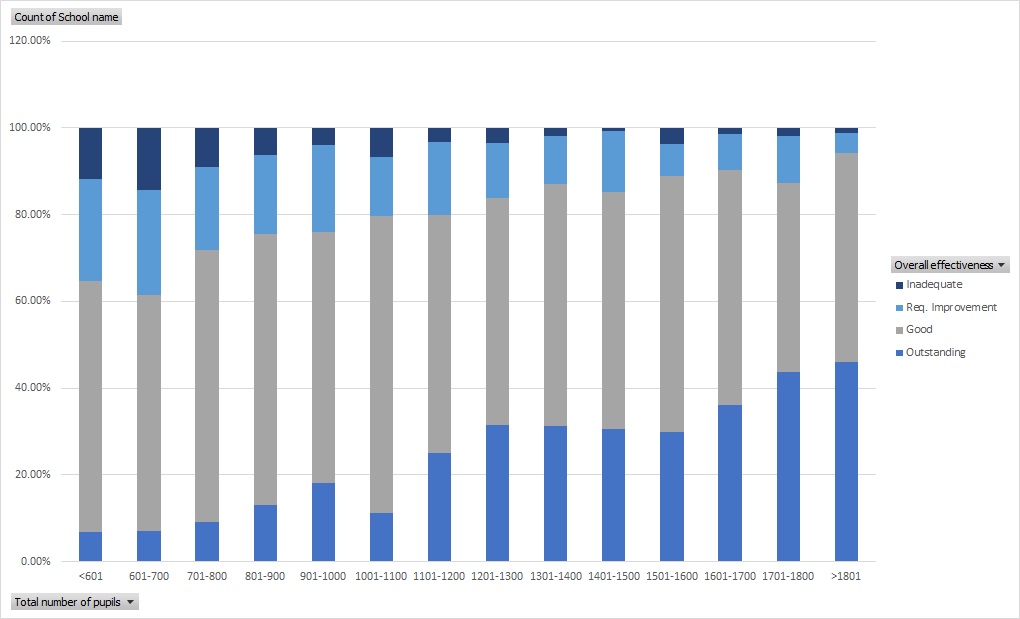

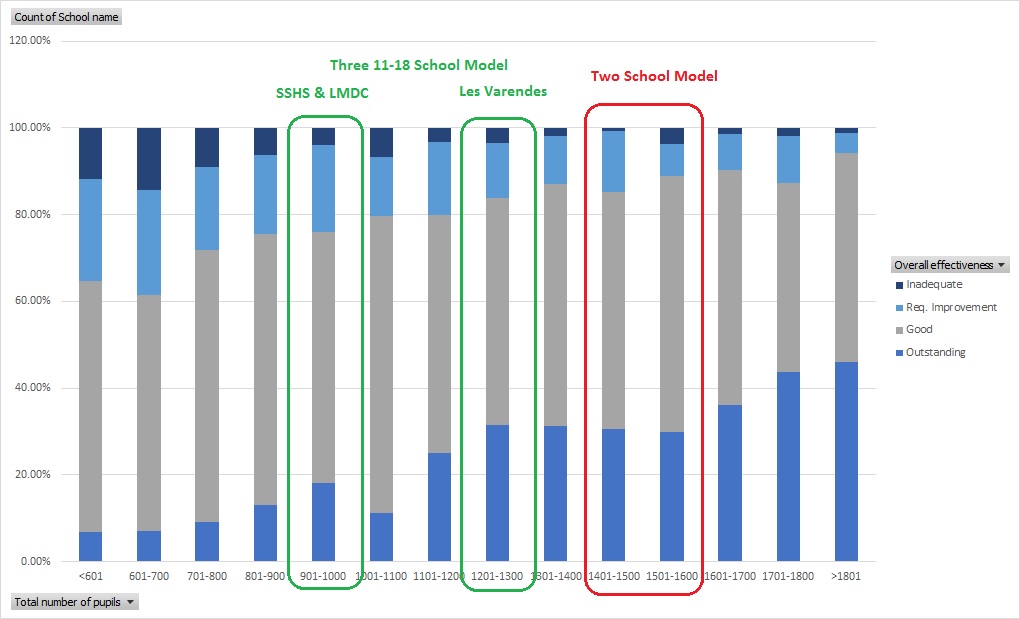

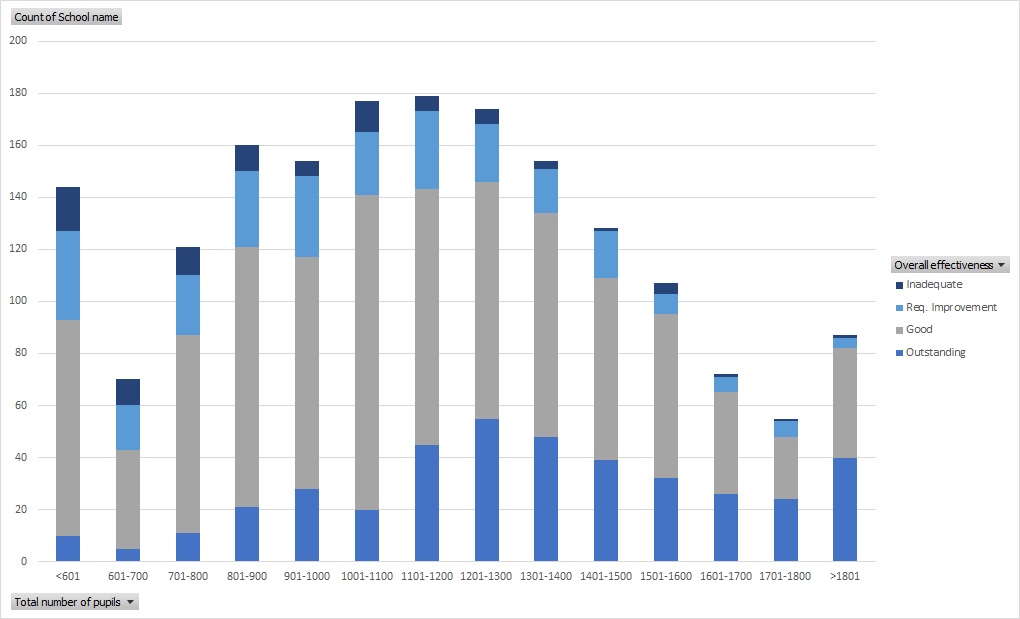

This would also not feature the perceived inequality of the previously presented three school model, with one 11-18 school and two 11-16 schools. In that model, a perfectly valid criticism against it was that the two 11-16 schools would inevitably have lower status, and consequently educational standards. Whilst it is perfectly possible to run 11-16 schools that offer a high quality of education, and examples of highly regarded 11-16 schools exist, critics frequently cite UK statistics demonstrating generally poor performance of 11-16 schools in Ofsted reports. These can be explained by several factors, among them, the reluctance of some teaching professionals to be limited to teaching to GCSE level only, and the absence of positive role models continuing their education to sixth-form level within the school.

The 3x 11-18 model has none of these issues: it is three, non-selective schools of equal status, offering the same standard of education to all. The only caveat, the requirement for specialisation at sixth form level at two sites, can be simply accommodated within the existing school estate. This specialisation cannot be considered a disadvantage, in fact the reverse. The experience in the UK is that parents seek out specialist schools, which are often considered as more desirable than standard comprehensive schools, and often oversubscribed as a result.

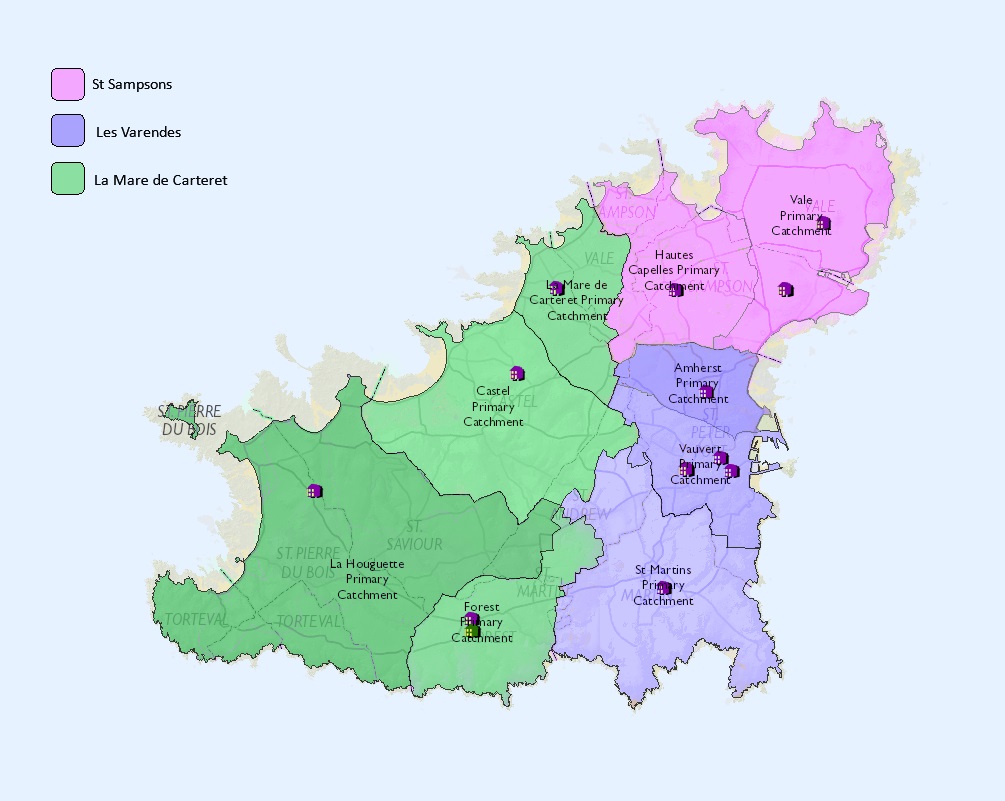

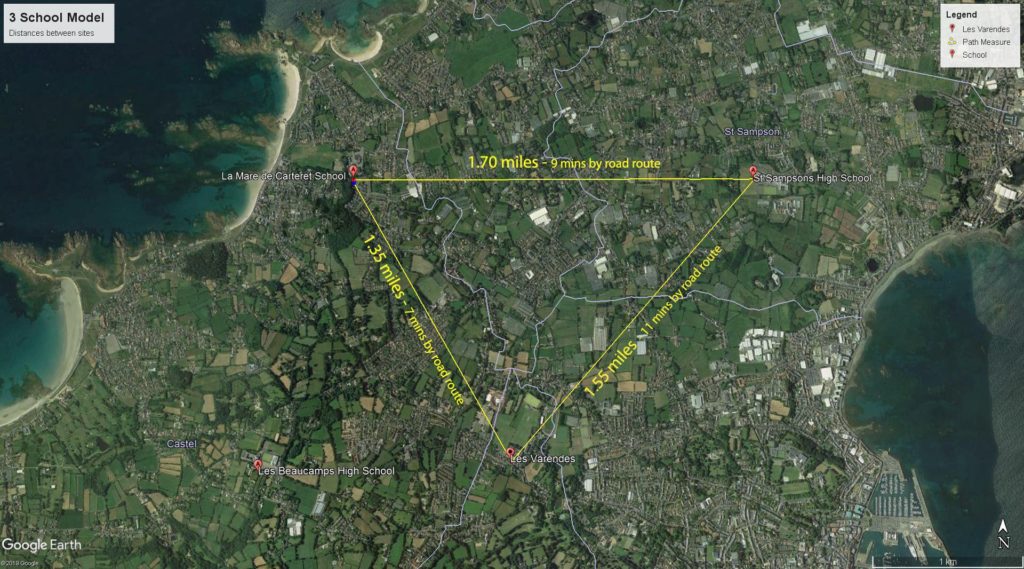

Moreover, the three school model happens to fit perfectly both with the currently available school sites, with the population distribution in the island, and including the requirement to provide new accommodation for the FE. The current CoFE operates in substandard buildings and is long overdue an upgrade.

For secondary schools, this has the effect of minimising travel distances, and maximising the opportunities for travel by foot, bicycle or bus to a local school. This is in stark contrast to the two-school model, with two poorly located schools, that would require very substantial structural changes to the transport routes for a large majority of pupils.

Since the road transport network in Guernsey is not well developed, in order to operate at all, the two-school model has a fundamental requirement for an unprecedented level of controlling regulations in order to minimise car use. The 3x 11-18 model has none of these problems: schools are located on existing sites, close to population centres where people live.

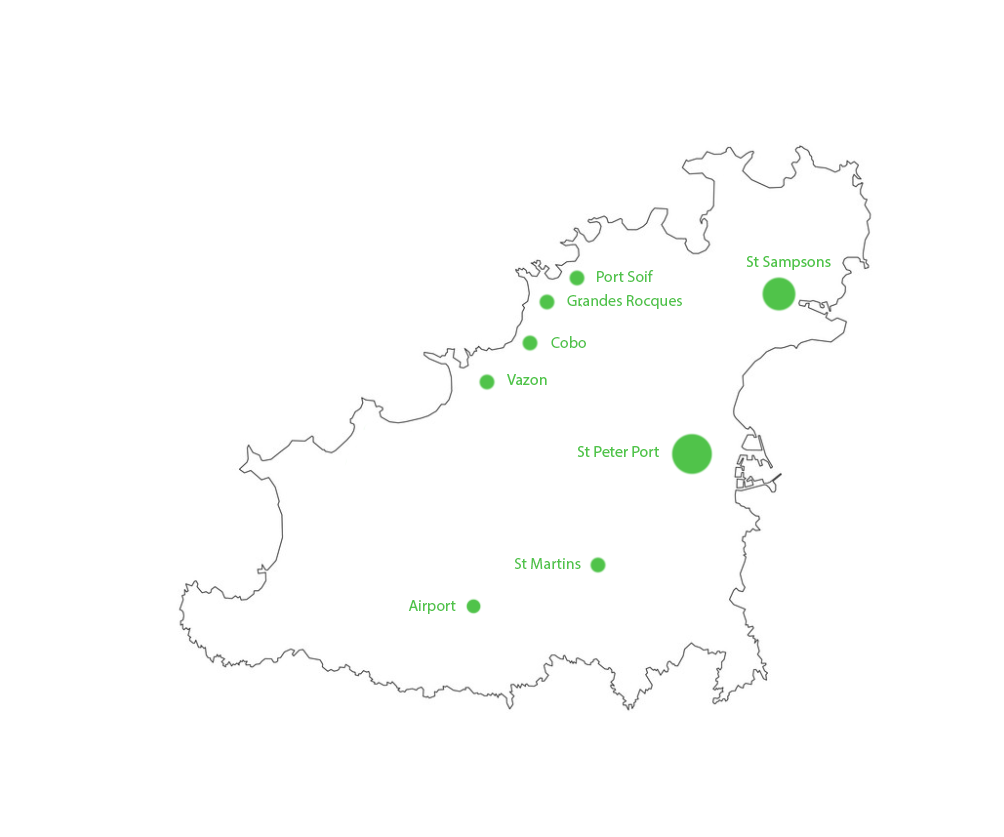

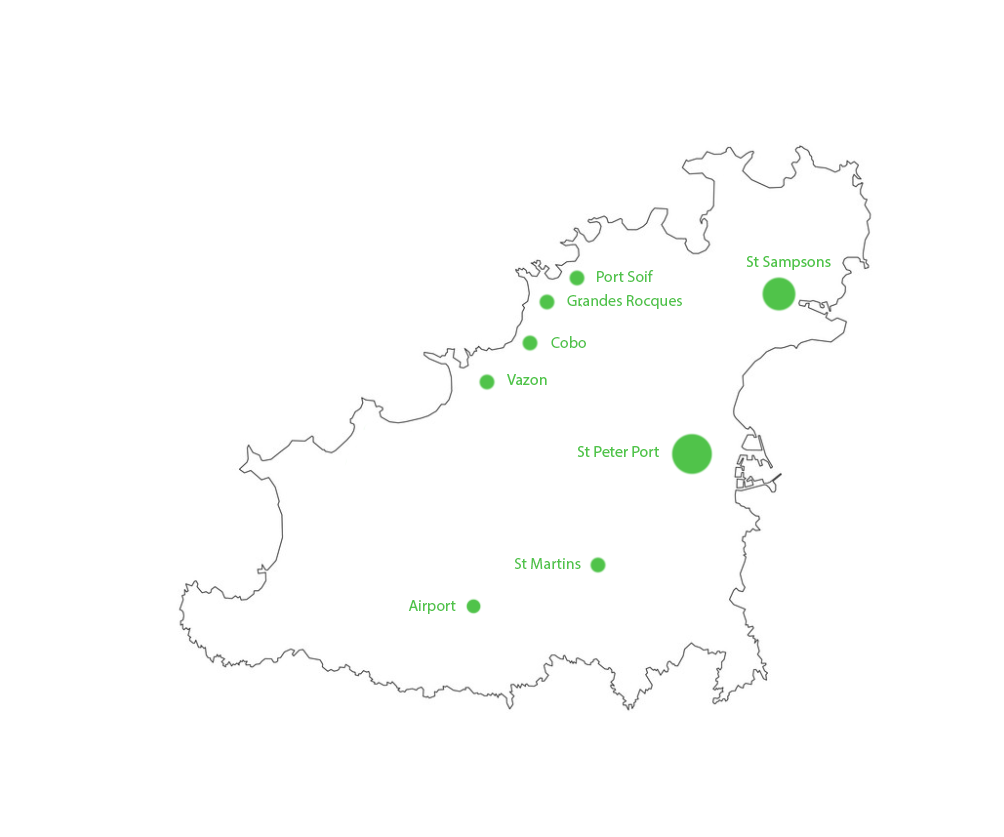

This diagram approximates some of the main populated centres in Guernsey (though it doesn’t capture the housing build spread out in the North of the island around St Sampsons) but does illustrate the main built up areas of housing:

Population Centres in Guernsey (Illustrative)

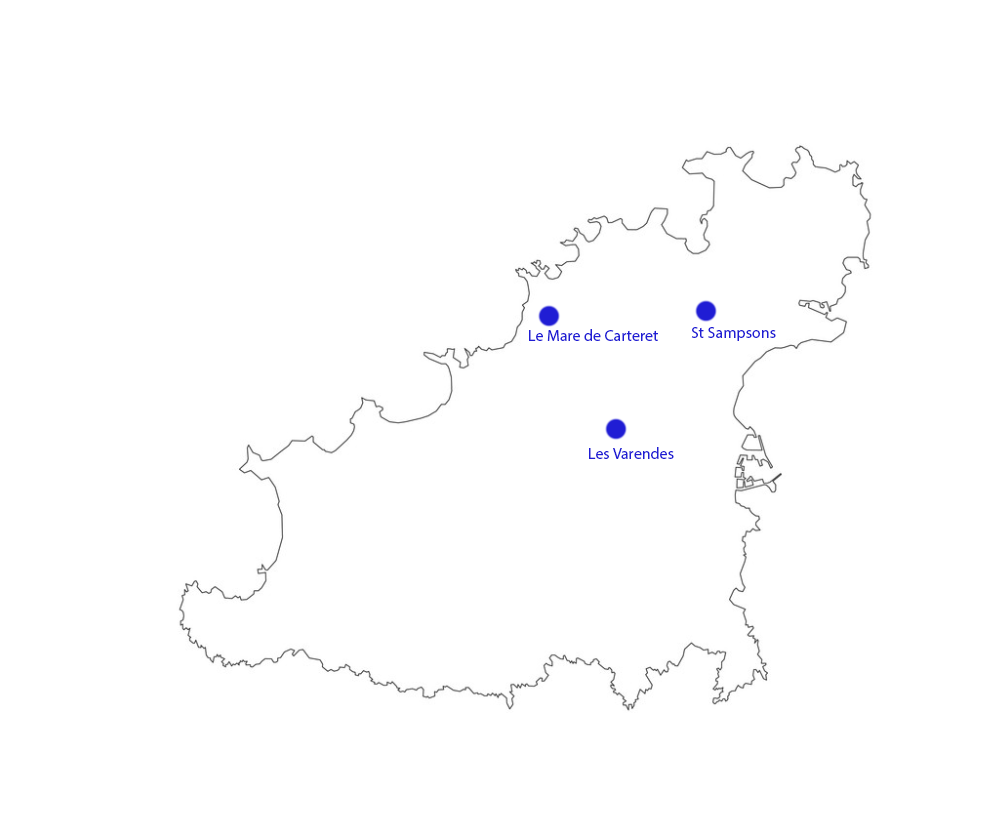

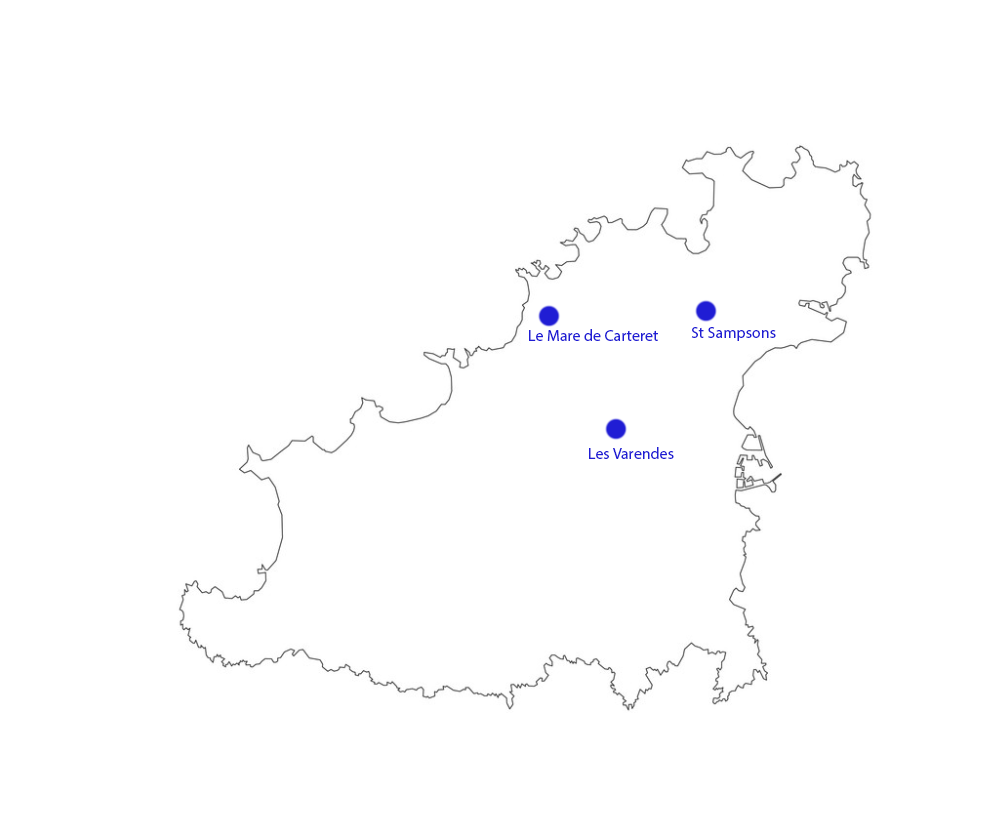

The 3 x 11-18 schools would be located close to those population centres, on existing school sites. All the schools are close to population centres, which would form the greater part of their catchment area.

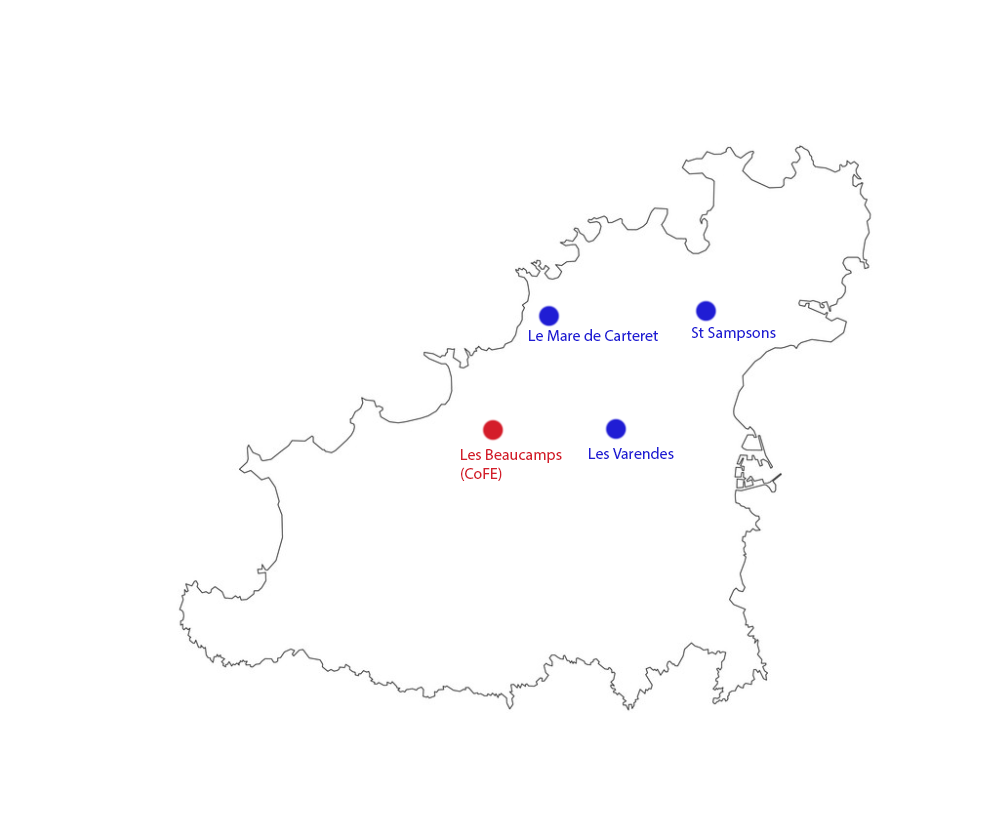

Location of three 11-18 schools The College of Further Education could then be located in the existing education building at Les Beaucamps, providing a modern, purpose built building that can be refurbished or extended to adapt to the needs of further education.

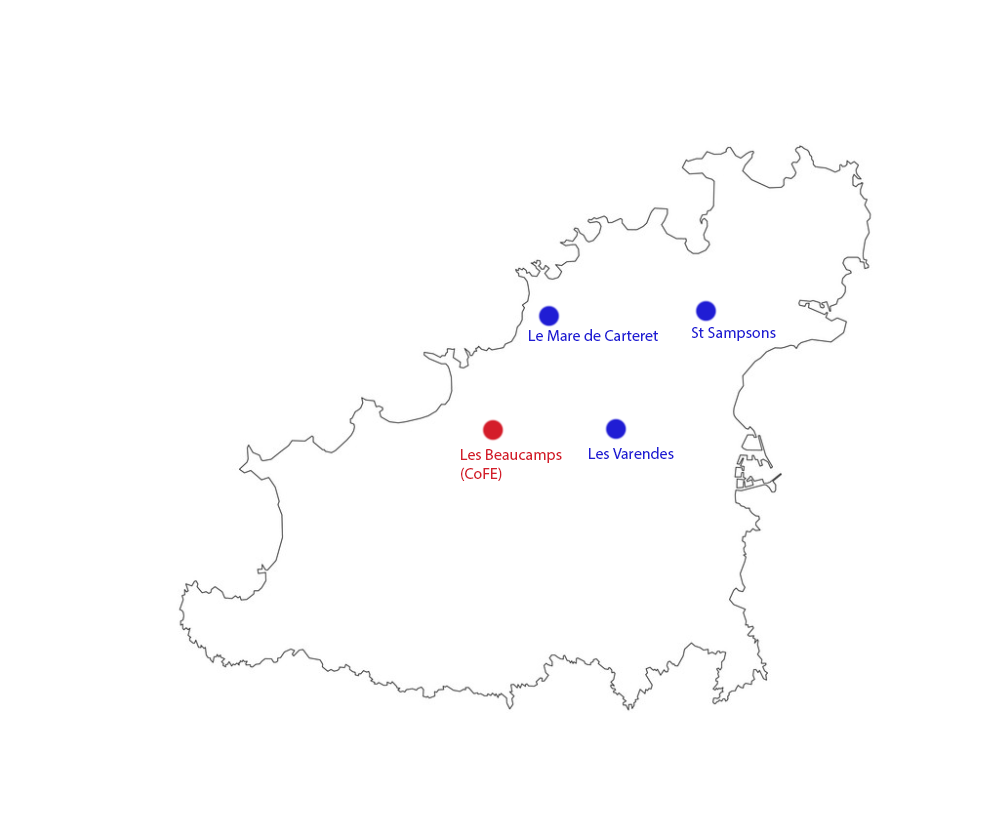

The College of Further Education could then be located in the existing education building at Les Beaucamps, providing a modern, purpose built building that can be refurbished or extended to adapt to the needs of further education.

Location of three 11-18 schools and new Guernsey Institute

Plans to redevelop the buildings at Le Mare de Carteret already exist, and can be updated and adapted for use as a new 11-18 school, rather than the originally planned 11-16 secondary school.

Academic Specialisation

In order to offer the full range of curriculum options across three sites, a moderate specialisation is required in two of the sites. This would mean that the existing 11-18 school at Les Varendes, the former Grammar School, could continue to offer a range of subjects and options, keeping the “jewel in the crown” provision that has served the island well. Unlike the two-school proposal, there is no need to “split up” or divide the current SFC into halves or thirds. This provides a central site with a broad A-level offering, with particular strength in traditional academic subjects.

To compete at the other two sites, specialist subjects at A-level only could be chosen that reflect the popularity of subject areas studied in the island. At GCSE level, all three schools would continue to offer a full “broad and balanced” comprehensive education.

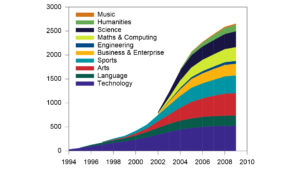

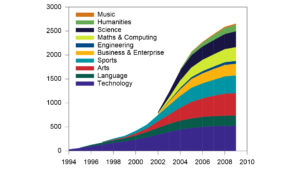

The UK has extensive experience with specialist schools, following the introduction of the Specialist schools programme in 1998. Under that mechanism, specialisms are generally quite narrowly focused, but importantly, all schools continue to offer the full National curriculum such that educational provision at GCSE is not reduced for pupils who do not take up the extended offerings provided in the school. The following chart shows the expansion of such schools in the UK since their introduction:

By Kanguole – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6005945

Due to size limitations in Guernsey, many schools with a narrow specialisations such as these are not possible. However, schools can combine more than one specialism. It is possible to select specialisms that match the demand in Guernsey and create world class schools in those areas. Using a consortium approach, these would be backed up by the strong provision already in place at Les Varendes. With a broad an balanced GCSE curriculum at all schools, there would be little requirement for any students to seek an out-of-catchment school placement, though this would be available for those that wanted to for any reason, including a desire to take advantage of the extended options at GCSE that could be made available. At sixth form, a change of school might be required to achieve the subject combination sought by each student.

In practice, this would mean that Les Varendes would continue to offer a broad range of A-levels, which as a former Grammar School, it already does. All the teaching staff, facilities, skills and support are already in place for this offering. The amount of relocation is minimised as in many cases, the staffing requirements remain unchanged.

To offer the same options at Le Mare de Carteret & St Sampsons, it is first necessary to assign an A-level specialism to each. All three schools would be required to continue to offer the National curriculum subjects at GCSE, the specialism would be in addition to that offering, and match popular option choices in the island, e.g.

- Les Varendes : Wide range of subjects available and IB

- La Mare De Carteret : Specialises in Sports and Business

- St Sampsons: Specialises in Music, Technology and Media

The actual specialisms would need to be introduced with consultation of teaching professionals, and with the knowledge of the likely popular option combinations that can be predicted.

Clearly with this arrangement, for some sixth-form students at Le Mare and St Sampsons, achieving their desired combinations at A-Level would require switching school, either full time or for a single option. This could either mean switching from one to the other, or switching to Les Varendes. The latter option would also be required for those students that wish to choose an unusual combination of subjects that could only be combined at a school offering a more general range of subjects.

The upside is, the specialisms at LMDC and SSHS could produce exceptional schools in those areas that match the best available nationally for those subject areas. This would be combined with the already excellent sixth form centre at Les Varendes, where the 2019 inspection noted ‘the percentage of students achieving A* to B awards is now significantly higher than in the UK’

With the newly created FE institute situated at Les Beaucamps, a further option to combine vocational courses with A-levels becomes available. With all these elements in place, the model could offer the best of all worlds.